“I Was Descending to the World of Yesterday”: The Night Strangler, 50 Years Later

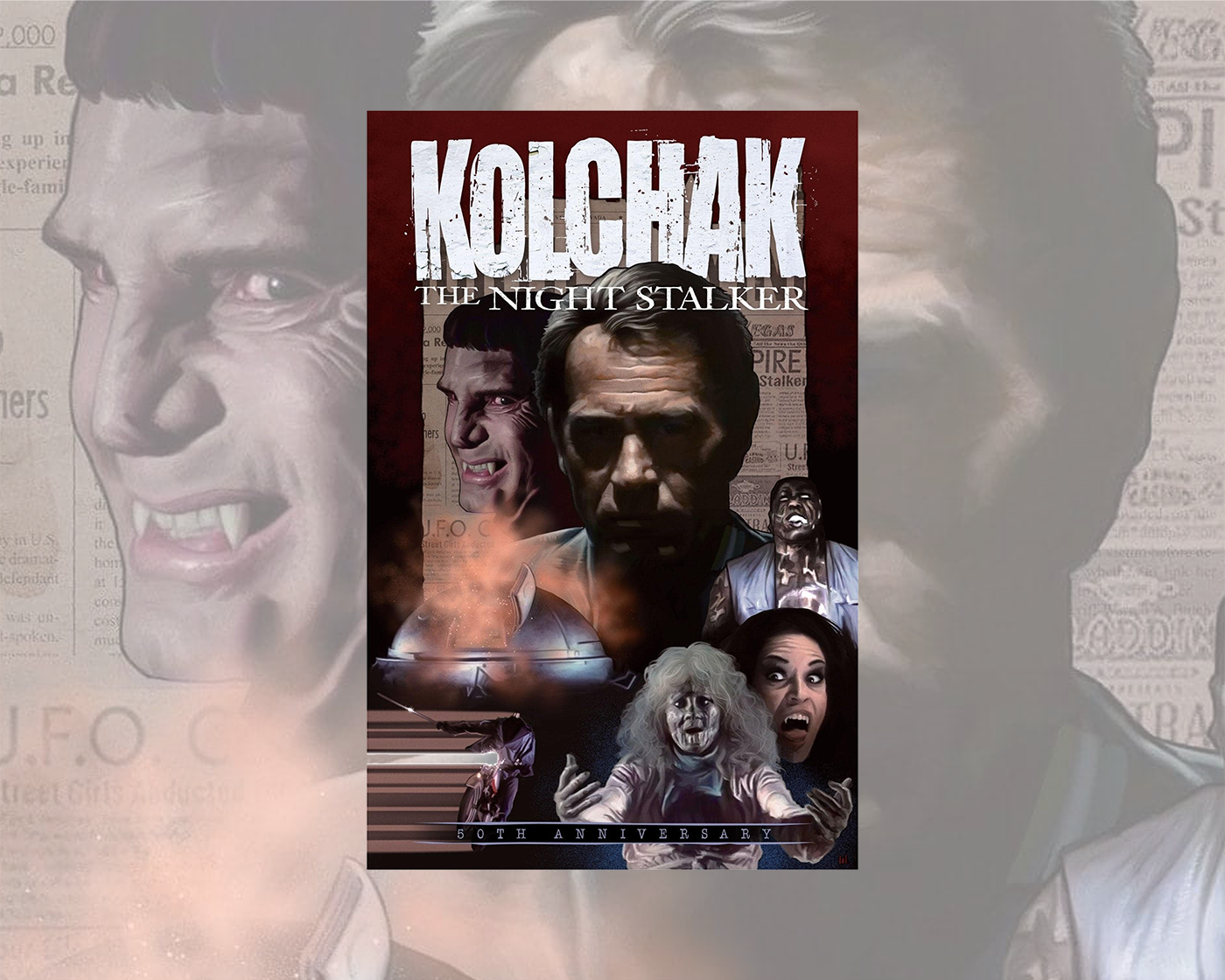

Get the Kolchak 50th Anniversary Graphic Novel

By Greg Cox

One of the minor banes of my life on social media is that whenever somebody mentions The Night Strangler online, people invariably “correct” them. “You mean The Night Stalker.”

No, we mean The Night Strangler, the second of the original Kolchak TV movies, now celebrating its 50th anniversary after first airing on ABC on January 16, 1973, when I was just 13 years old. A direct sequel to the previous year’s The Night Stalker, then the highest-rated TV movie in history, Strangler brings back Darren McGavin as indefatigable reporter Carl Kolchak, a year after staking an honest-to-goodness vampire in Las Vegas and now investigating a new string of mysterious murders, this time in Seattle. No surprise, Kolchak soon discovers that he has another seemingly preternatural killer on his hands, much to the exasperation of his long-suffering editor, Tony Vincenzo, played once again by Simon Oakland.

Strangler hews closely to what made Stalker work so well. A crackling script by the legendary Richard Matheson (who also scripted the previous film, based on a then-unpublished novel by Jeff Rice), full of punchy dialogue, colorful characters, and genuine suspense; Bob Cobert’s dynamic musical score, which manages to be bouncy, hard-boiled and eerie, often at the same time; and, of course, McGavin’s now-iconic portrayal of Carl Kolchak: cynical, irreverent, and dead set on uncovering the truth, no matter how many people he has to piss off along the way. Directed this time around by Dan Curtis (celebrated creator of Dark Shadows), Strangler also boasts an embarrassment of riches when it comes to familiar faces among the supporting cast, including John Carradine, Margaret Hamilton, Al Lewis, and Richard Anderson. Where else can you see Count Dracula, the Wicked Witch of the West, Grandpa Munster, and Oscar Goldman in the same movie? With Anderson playing the titular Strangler, Dr. Richard Malcolm, only a few months before he started bossing around the Six Million Dollar Man. Matheson even works in a cute in-joke alluding to Carradine’s Transylvanian resume:

“He may be old, but his fangs are potent.”

Beyond all that, I’ve always had a special fondness for The Night Strangler since it’s very much set in my own backyard. Growing up around Seattle, I had never seen a horror movie set in my hometown before, let alone one so deeply rooted in our local landmarks and history. Pioneer Square! The Space Needle! The Monorail! The Underground City!

And then there’s the classic moment when Vincenzo takes Kolchak off the murder case and assigns him to instead cover the Daffodil Festival in nearby Puyallup, Washington, provoking Kolchak’s befuddled response.

“Puyallup?”

For the record, I was born in Puyallup, my parents were born and raised there, and, yes, the Daffodil Festival is a real event that I attended every year, so my teenage jaw dropped to hear it referenced onscreen. And, even more amazing, Darren McGavin actually pronounced Puyallup correctly!

Little did I know at the time that McGavin had spent his teen years drifting around Tacoma, not far from Puyallup. No wonder his tongue did not trip over the name. (Unlike Johnny Carson, who mangled it on The Tonight Show around the same time.)

These days, besides being a cult classic and key installment in the Kolchak saga, The Night Strangler also serves as a nostalgic time capsule of 1970s Seattle, before grunge, Microsoft, Amazon, and Starbucks. Within the constraints of ABC’S standards & practices, the movie accurately captures the sleazy, seamy vibe of Pioneer Square back in the day, when it was indeed known for its shady massage parlors, XXX-rated movie theaters, strip clubs, and streetwalkers. (Think Times Square, pre-Giuliani.) Watching it today takes me back to the days before art galleries, funky coffee shops, and concerns about gentrification. The movie’s “Omar’s Tent,” with its endangered exotic dancers, would have fit right in back then.

Not that the movie doesn’t take some liberties. Like most movies and TV shows set in Seattle, it can’t resist treating the monorail as a common means of mass transit, as opposed to a glorified tourist attraction left over from the 1962 World’s Fair. (Kolchak takes the monorail home from work at one point.) And, of course, Louise Harper, the plucky coed/belly dancer Kolchak takes a shine to, lives on a scenic houseboat, unlike most real-life Seattle residents. Meanwhile, we can probably forgive the movie for inventing an imaginary newspaper, The Daily Chronicle, since I imagine neither The Seattle Times nor The Seattle Post-Intelligencer would have liked being depicted as taking part in a cover-up!

Which brings us to the Underground Tour.

In the movie, Kolchak eventually tracks Malcolm, revealed to be an undying alchemist in need of freshly tapped human blood for his elixir of life, to a secret lair beneath the Seattle Underground, which is also a real thing. When the downtown business district burned to the ground in the Great Seattle Fire of 1899, it was rebuilt 20 feet higher to avoid water-table issues that had plagued the district since its founding. As a result, ground floors became basements, sidewalks became underground passages, and these eventually fell into disrepair over the ensuing generations. Guided tours of the Underground began in 1965 and have been a popular tourist attraction ever since. (Bill Speidel, a noted Seattle historian and the founder of the tour, makes a cameo as himself in the movie; he’s the bearded gentleman giving a lecture when Kolchak and Louise meet to explore the Underground for the first time.)

Speaking from experience, the tour is quite entertaining, largely because of the guides’ colorful tales of frontier Seattle’s bawdy past, but Kolchak fans should adjust their expectations: the actual Underground is nowhere near as spooky or impressive as the one seen in The Night Strangler; in real life, it’s basically a maze of interconnected basements that used to be storefronts, cluttered with vintage debris.

Granted, the movie’s first glimpse of the Underground, when Kolchak and Louise take the official tour, looks pretty much like the real thing, but any resemblance to reality vanishes in the movie’s chilling final act, when Kolchak descends via a secret passage to discover what looks like an entire city block of ghost town buried deep beneath the Underground, complete with two-story buildings, cobblestone streets, abandoned carriages, a working cage elevator, mummified corpses, and copious amounts of swirling dry-ice fog. It’s a spectacular, memorable, evocative milieu, but also an utter flight of fancy. Matheson attempts to rationalize this by explaining that Kolchak has stumbled onto an unknown section of Old Seattle beneath the regular Underground, but this doesn’t really hold up to close examination. How can there be another layer of buildings below the ones we know about, let alone such a sprawling multi-level site?

Then again, who wants to see Kolchak face off against Malcolm in some musty old basement? The Underground city of The Night Strangler is way more breathtaking than the genuine article. Just don’t expect to find it if ever you go sightseeing in Seattle.

Tucked between the groundbreaking first movie and the tragically short-lived weekly TV series, The Night Strangler is basically the “Jan Brady” of Kolchak stories, too easily overlooked. But it deserves much better than that. It’s a compelling, clever, and hugely entertaining horror-thriller that still holds up after a half a century.

Even if you’ve never heard of Puyallup.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Greg Cox is the New York Times bestselling author of numerous novels and short stories, including the official movie novelizations of War for the Planet of the Apes, Godzilla, Man of Steel, The Dark Knight Rises, Ghost Rider, Daredevil, and the first three Underworld movies. He has also written books and stories based on such popular series as Alias, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, Farscape, The 4400, Leverage, The Librarians, Riese: Kingdom Falling, Roswell, Star Trek, Terminator, Warehouse 13, The X-Files, and Xena: Warrior Princess. He has received six Scribe Awards from the International Association of Media Tie-Writers, including one for Life Achievement.

“All the creators involved understood what was unique about Kolchak. They got him. They love him. They brought him back to life in a way I’d not thought possible.” – Corrina Lawson, LitStack Review